The eucalyptus tree has many faces with more than 700 species spread around the world — mostly found in Australia, but reaching as far as the Philippines. Of the hundreds of species, only a few call California home. The most popular of eucalyptus trees in the Golden State is the Eucalyptus globulus, better known as the Tasmanian blue gum — a tree that many consider to be “the world’s largest weed.” Other popular species in our state include the red ironbark and silver dollar eucalyptus. If you call California home, then the eucalyptus tree is no stranger. They line our freeways and cluster around our parks and structures. But where did they all come from and why do we keep hearing about them falling on streets, structures, and in worse case scenarios, on local bystanders?

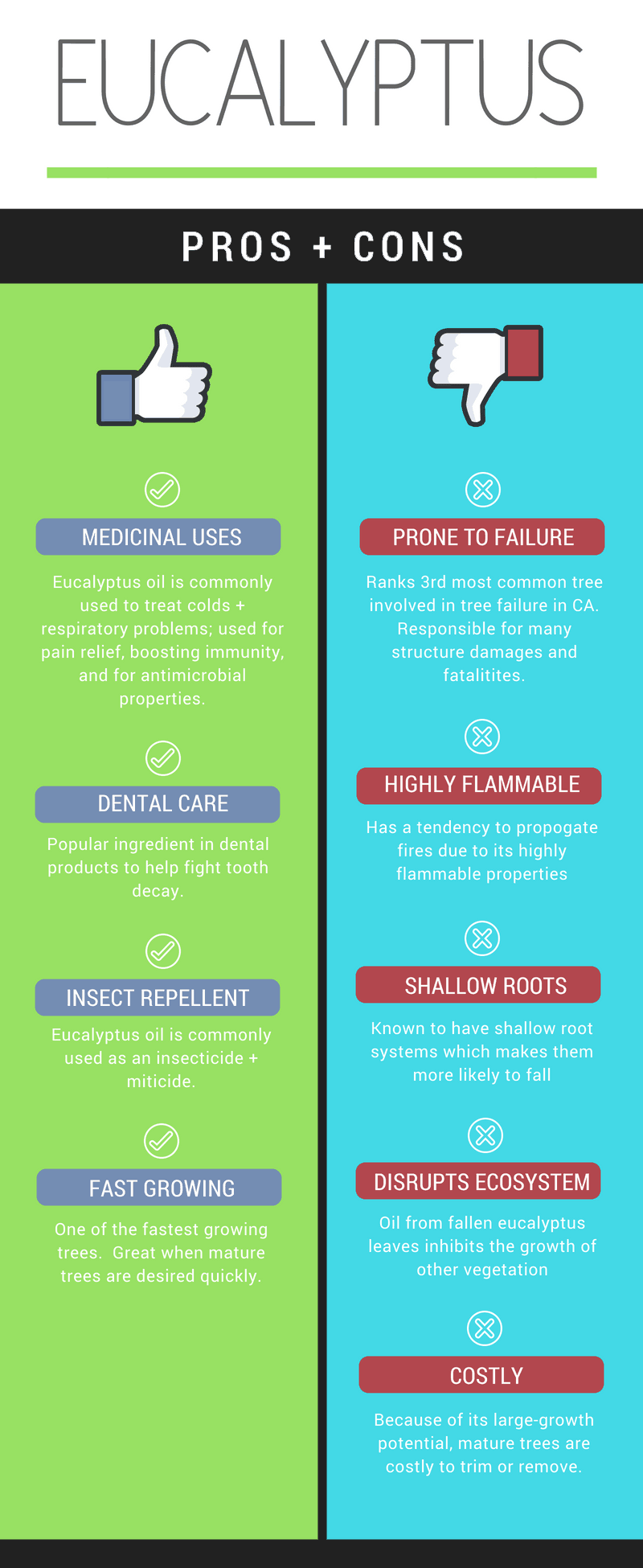

Originating from Australia, the eucalyptus comfortably found its home in California less than two centuries ago. Quickly becoming widespread throughout California, the adaptability of the eucalyptus tree gives them the advantage of growing where other plants are unable to grow, such as in lands destroyed by mining or poor agricultural. They serve medicinal uses, such as antiseptics, decongestants, and stimulants; and are also used in foods, perfumes, and toothpastes. Although fascinating and useful, the hazards from the eucalyptus have become more prevalent in their foreign home, so much so, reevaluating their vast spread throughout the state has now become a great concern for local communities.

Foresters and industrial companies in Europe were first highly intrigued in this rare find as early as the 1770s. The eucalyptus was desirable for its purposes of making various material such as timber, fuel, medicine, wood pulp, honey, and medicinal and industrial oils. Decades later the California Gold Rush began to unfold in the late 1840s. Demand for wood for construction and fuel was exceedingly high, and deforestation became a huge concern. Soon the California Tree Culture Act of 1868 was enacted, which encouraged people to plant more trees, especially along roads. The state needed trees — and fast!

This is where the quick-growing eucalyptus made its pandemic arrival to California. Industrial companies were so impressed by the growth speed of these trees that people began planting them in droves. As soon as the trees were cut down, even at their roots, they would sprout quicker than expected. This made the eucalyptus incomparable to other native and non-native tree species.

But as helpful as the trees were for a time, they later became a surprising threat. A mature eucalyptus tree averages 150 to 200 feet in height. It typically outgrows its own strength, bearing more weight on the limb than it can actually support, leading to “sudden branch drop” — as the name implies — when a limb suddenly drops with no physical forewarning. Adding to this issue is the onslaught of rain, especially when the tree has been living in a dry terrain, like Southern California. While the eucalyptus can withstand living in drought regions, as with all trees, water-deprivation weakens its structure. Then when rain does come, it has a dangerous habit of soaking up heavy amounts of water to compensate for the past dry period. This overindulgence causes its already-too-heavy limbs to fail with the added water weight. Unfortunately, surrounding areas around school buildings, parks, and business structures can become danger zones from the sudden drop of the eucalyptus tree, as they can tragically cause harm to buildings and local bystanders — an all-to-common local news story, especially during Californian storms.

People and buildings of our communities are not the only ones affected by the eucalyptus. Because it is a non-native plant species, they can wreak havoc among the indigenous plants and animals in its surroundings, as it rivals them for nutrients in the soil. By manipulating the soil’s nutrient levels that the local environment survives on, these invaders disrupt the natural ecosystem of the native plant species and animals, forcing them to leave their homes. The leaves of the eucalyptus tree also contains a powerful oil — one that is popular amongst essential oil users. When fallen eucalyptus leaves collect on the ground, it is the oil that is the main culprit for changing the surrounding ecosystem by inhibiting vegetation growth and changing the chemistry of the soil. Furthermore, the bark strips from the eucalyptus are severely flammable, fueling local brush fires that Californians have to deal with on a yearly basis.

Trees serve best in the soil their roots were originally planted in. When they are uprooted to be planted in foreign lands for their exotic aesthetics and potential benefits, non-native plant species can sometimes cause a more negative impact than a positive one to their new environments. Known for its tall, gangly beams of perfect shade, it’s unfortunate that the eucalyptus tree has become more hazardous than beneficial to its California home. They add beauty, and local Californians all grew up with the familiar sight of them along our roads and freeways. Friend or foe? It depends on the situation and the use, but here’s what we have to say.

for health benefits through its oils — FRIEND

as landscape around roads and freeways — FOE

as landscape for your home — FOE

as a nice shade tree for a park — FOE

as a green addition to a school yard — FOE

for a cute cuddly koala — FRIEND

So while the eucalyptus tree does have its well-known benefits, especially for hungry koalas at the San Diego Zoo, and they do play their part in adding beautiful greenery to this region, using them as fillers in our landscape may not be the best choice anymore. Friend or foe? It’s an ongoing debate, but you be the judge.